Nickel is a critical mineral with ~70% of current demand being dominated by stainless steel followed by 25% for manufacture of alloys, special steels, and coatings, and 5% for electric batteries. While demand from stainless steel and alloys will likely remain robust in the medium-term, significant demand growth is expected to arise from nickel’s application in lithium-ion batteries due to electric vehicles’ (EVs) penetration and changing battery chemistry.

Nickel is predominantly mined from sulfide and laterite ores. Nickel laterite ores are primarily found in southeast Asia while sulfide ore deposits are mostly located in countries such as South Africa, Canada, and Russia. Nickel sulfide ores are higher grade ores with higher mining but lower processing costs. In contrast, laterite ores are typically lower grade and require economies of scale for acceptable mining costs but will usually incur higher operating costs. Historically, most nickel production came from sulfide ores but rapid growth in the nickel pig iron (NPI) industry in Indonesia has resulted in ~70% of nickel production coming from laterite ores today. Indonesia predominantly supply NPI to its leading trading partner, China, as lower-grade intermediates for stainless steel production. Some of shift in ore type has also impacted the overall global nickel production share of top mining companies such as Vale, Norilsk Nickel, Jinchuan Group, Glencore, and BHP which shrank from more than half in early 2010s to just 24% today.

In 2020, global nickel mine production reached around 2.5 million metric tons (Exhibit 1). Southeast Asia accounted for the largest share of global nickel production with Indonesia taking ~33% followed by 12% from Philippines, and 8% from New Caledonia. Further, countries such as Russia, Canada, Australia, and China also accounted for 11%, 7%, 6%, and 4%, respectively, of the global nickel production.

Nickel has basically two grades − Class I and Class II. Class I has higher purity with nickel content of >99.98% and is used in batteries while Class II nickel primarily finds application in stainless steel. Nickel pig iron and Ferro-Nickel (FeNI) are examples of Class II nickel with nickel content of 10% and ~40-60%, respectively. Further, Class I nickel is generally produced from sulfide ores and has higher production costs than Class II nickel which usually comes from laterite ores. Class I nickel can also be produced from laterite ores but requires additional costs to upgrade.

EV batteries will particularly drive demand for Class I nickel in the upcoming years but supply security will likely be challenged due to several reasons. First, lower nickel prices have resulted in insufficient investments in class 1 nickel production due to its high initial investment requirements. Second, with only a few countries accounting for a large share of global nickel production and processing, there is a high degree of geopolitical risk associated with supply. For example, in 2014, Indonesia enforced a 2009 ban on the export of nickel ore, which was briefly relaxed in 2017 but reinstated as of January 1st 2020, impacting China which is their biggest consumer.

Further, factors such as longer lead time of around 12-20 years for new nickel mining projects coupled with increasing environmental, social, and governance (ESG) regulations and costs could hinder commissioning of new nickel mining projects in the coming years. For example, the Philippines plans to impose stricter regulations for the mining sector that may force some mining sites to close.

Looking at the near-term projects, most of the Class I nickel supply growth is expected to come from laterite ores in both Indonesia and Philippines via the high pressure acid leaching (HPAL) process. There are two HPAL nickel plants already under operation in Philippines as well as four HPAL plants with combined capacity of 155,000 tons under construction in Indonesia (Exhibit 2) with expected start-ups between 2021-2025. Further, in 1Q 2021, a Chinese company, Tsingshan, which is the world’s largest nickel producer, announced that it will supply a total of 100,000 tons of nickel matte (>75% Ni) based on converted nickel pig iron (NPI) from its operations at Indonesia Morowali Industrial Park (IMIP) to Chinese companies Huayou and CNGR Advanced Materials. These companies will further process nickel matte to produce battery-grade nickel sulphate on a regular basis. Once operational, the project can be a game changer in overall Class I nickel production. Further, beyond 2025, any other supply deficit will need to be met with new investments in nickel mining projects in countries rich in sulfide ores such as Russia and South Africa. Russian mining company Nornickel is already one of the biggest global producers of class 1 nickel.

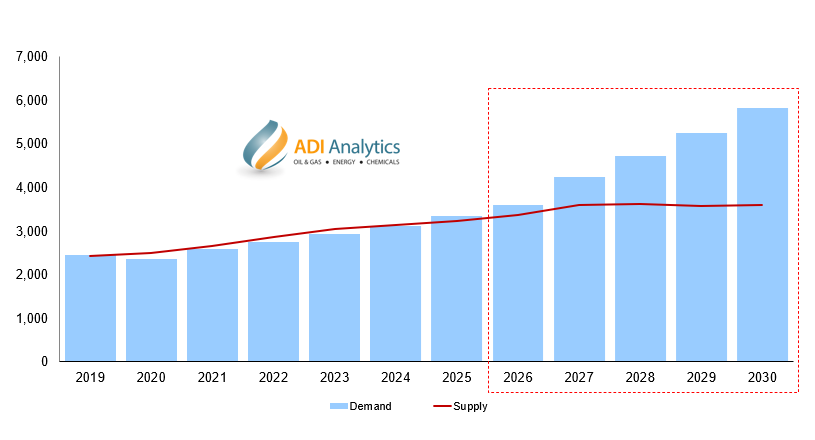

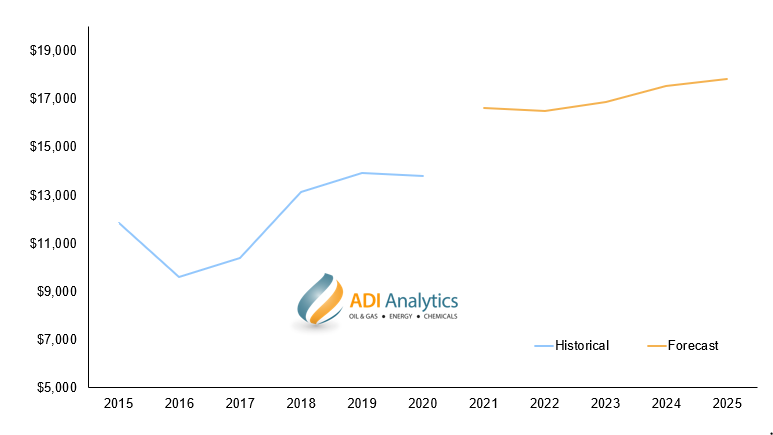

However, lack of an adequate and firm pipeline of projects needed to meet projected demand growth from EVs over the next decade will continue to result in nickel supply uncertainty in the medium-to-long term. Nickel is called the devil’s metal due to its high price volatility. Changing policies around mining and exports in major producing countries have led to price variations in recent years and we will continue to witness volatility and a gradual uptick in nickel prices going forward (Exhibit 3).

ADI is launching a multi-client study – “The New Frontier: Critical Minerals & the Energy Transition” – which is focused on a comprehensive assessment and outlook for critical minerals supply and demand through 2030. This 12-week long multi-client study process builds on ADI’s extensive research and deep expertise in metals, minerals, mining, mineral processing, and energy transition. The study will be based on in-depth primary and secondary research and supply and demand modeling and analytics. Please download the multi-client study prospectus – “The New Frontier: Critical Minerals & the Energy Transition”– and contact us to learn more.

Visit the rest of our blog series, Mining and Metals, to learn more about other critical minerals for the energy transition and stay tuned for upcoming blog posts.

– Swati Singh and Jacqueline Unzueta