Lithium-ion batteries are used everywhere, but what does that have to do with cobalt? A lot. In fact, lithium-ion batteries accounted for 57% of the total cobalt demand in 2020. One-fifth of the material in a typical lithium-ion cathode is cobalt, and battery manufactures heavily use it due to its boosting effect in battery charge rates and resistance to cathode corrosion. Despite cobalt’s superior performance, battery manufactures are looking to reduce their cobalt dependency.

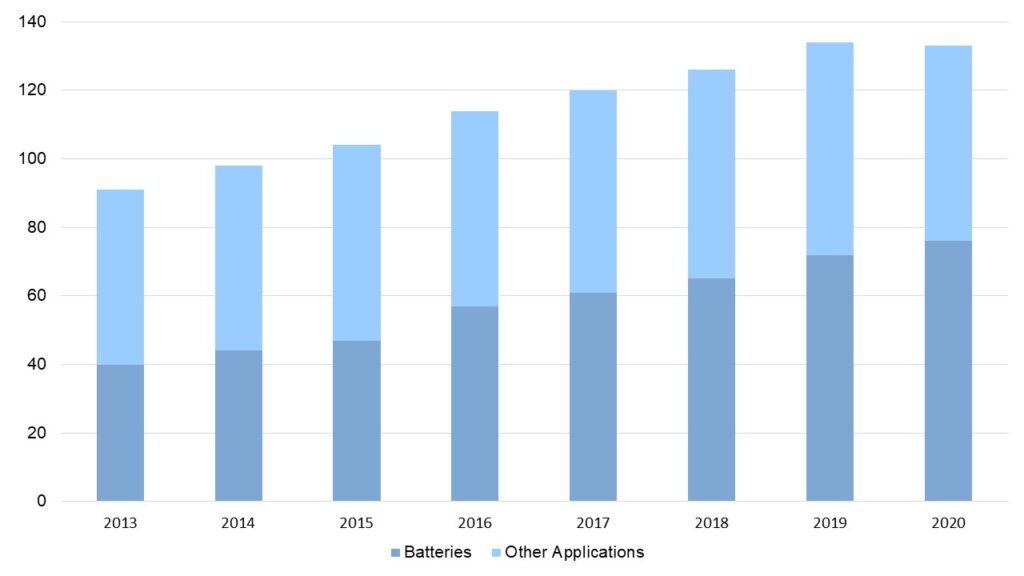

Concerns related to cobalt’s high cost, unethical mining practices, and tenuous global supply chain have inspired innovative battery alternatives that could drastically lower the demand of cobalt in the future. Some companies such as First Cobalt doubt the success of battery manufacturers and end-users eliminating cobalt from future battery supply due to cobalt’s historically strong demand and past failed attempts to eliminate cobalt from batteries. The global demand of cobalt has increased markedly in recent years, with all major uses driving its growth. Overall, the cobalt market has grown at an annual rate of more than 5% since 2013 (Exhibit 1).

Ever so, many stakeholders believe that cobalt will continue to be a critical mineral during the energy transition and electric vehicle boom. This is why First Cobalt has plans to expand their production of battery grade cobalt sulfate in North America by October 2022. In November 2019, Glencore halted its operations at one of the world’s biggest cobalt mines, the Mutanda mine in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, after prices collapsed and the cost of the project increased. However, Glencore recently also announced its intention to resume operations at the Mutanda mine by the end of 2021 to allow the return to production by 2022. The reopening of the mine was made with the confidence that electric vehicles will continue to drive demand for cobalt. However, the closure of the Mutanda mine and the current lack of new cobalt projects pose challenges related to a potential supply deficit.

If Glencore fails to restart the Mutanda mine by 2022, then the anticipated cobalt supply deficit will likely reach 11,000 metric tons by 2024. In 2020, the cobalt mine production fell 6% from 2019 levels largely because of the Mutanda mine closure. On the other hand, Glencore continued to mine cobalt at their Katanga Mining assets in the Democratic Republic of Congo. The Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) accounted for 66% of the global cobalt supply or 96 kt in 2020. Seventeen percent of the DRC supply in 2020 originated from the Tenke Fungurume mine operated by China Molybdenum (CMOC). Eleven percent of the DRC supply in 2020 originated from the Metalkol Roan Tailings Reclamation (RTR) project operated by ERG. Smaller operations accounted for approximately 9% of the DRC output for 2020, while artisanal sources remained subdued due to low cobalt price levels and the COVID-19 pandemic.

Cobalt prices have been volatile between 2013 and 2020 ranging from $20,000 to $95,000 per metric ton (Exhibit 2). An enormous uptick in cobalt price occurred in the first quarter of 2017 due to a 63% increase in global sales of electric vehicles during that year. Prices continued to rise in 2018 to almost $95,000/t, a ten-year high. However, demand became sluggish in the successive years and the market became over-supplied. Prices crashed in 2019, which was the year that Glencore decided to halt operations at the Mutanda mine.

Cobalt prices are expected to continue rising in the short term, but stronger prices are still needed to motivate mining operators to start new projects and induce new supply. Despite the threat of being completely replaced by other critical minerals in lithium-ion battery production, cobalt prices are forecasted to rise $29.91/lb in 2025, which is a 27% increase from the current price of $23.81/lb. The introduction of cobalt-free batteries may not be detrimental to the market as battery manufacturers will have to consider the cost of alternative materials and the overall battery performance. For example, some cobalt-free batteries have a higher carbon footprint compared to lithium-ion batteries that contain cobalt. Innovation is picking up pace though, and cobalt-free battery alternatives with lower manufacturing cost and higher performance could be introduced and widely adopted in the near to far future.

In July 2020, a group of researchers from the University of Texas at Austin developed a cobalt-free battery without compromising performance. Arumugam Manthiram and his team reported that their cobalt-free battery design is the first to not have the common drawbacks such as low energy density and short battery life. Manthiram hopes to commercialize his cobalt-free cathode and present it to current EV manufacturers. There are many innovators like Manthiram who have the same goal, but the amount of time and billions of dollars spent perfecting cobalt cathode chemistries cannot be overlooked. As a result, new cobalt-free battery players will experience some industry inertia but penetrating the market can become a commercial reality.

ADI is launching a multi-client study – “The New Frontier: Critical Minerals & the Energy Transition” – which is focused on a comprehensive assessment and outlook for critical minerals supply and demand through 2030. This 12-week long multi-client study process builds on ADI’s extensive research and deep expertise in metals, minerals, mining, mineral processing, and energy transition. The study will be based on in-depth primary and secondary research and supply and demand modeling and analytics. Please download the multi-client study prospectus – “The New Frontier: Critical Minerals & the Energy Transition”– and contact us to learn more.

Visit the rest of our blog series, Mining and Metals, to learn more about other critical minerals for the energy transition and stay tuned for upcoming blog posts.

– Jacqueline Unzueta & Swati Singh