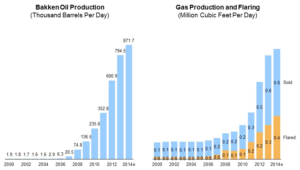

In 2014, almost one-third of natural gas extracted in North Dakota was lost to flaring. Flaring is when the gas is burned at the well instead of being commercially used. Flaring is more environmentally friendly than venting excess natural gas into the atmosphere. When natural gas is vented, the pollutant that enters the atmosphere is methane. When the gas is flared the byproduct is carbon dioxide. Methane is 25 times more potent of a greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide is and thus, is worse for the environment. Although flaring is less environmentally damaging, it is still a waste of valuable energy resources.

The North Dakota Industrial Commission (NDIC) has set goals to reduce flaring to 10% of extractions by 2020. More than one-third of flared gas could be avoided by building more pipelines constructed. Building a pipeline is difficult to do as it requires many government permits, a lot of time, and landowner permission. Although pipelines are slowly being built to accommodate the increased production of natural gas, there are a few ways to use natural gas that is being flared instead of transporting it through traditional pipelines. A few examples include small-scale gas to liquids (GTL), virtual pipelines, gas to wire, and gas to chemical technologies all of which are being developed to target the gas flaring market.

One of the first options is GTL. Gas to liquids plants take natural gas and produce valuable fuels, such as diesel fuel, which can be shipped readily without infrastructure changes. Historically, these plants have been large and required a large amount of capital. Although efforts to develop small-scale GTL plants are underway by companies such as Velocys and Compact GTL, the sector is struggling. We have seen two companies, Sasol and EmberClear, cancel their GTL projects in the United States sized at $11 billion and $1 billion, respectively. The high level of capital expenditure associated with these projects, along with the narrowing gap between the price of oil and natural gas are to blame for the cancellations as we have covered a few weeks ago.

A second option is using virtual pipelines. Virtual pipelines give customers, who are not connected to natural gas pipelines, access to natural gas. Through the use of compressor stations and heavy duty trucks that haul compressed natural gas to customers, virtual pipelines are able to provide consumers with a steady supply of natural gas. A heavy-duty truck will leave its home base filling station, conceptually located at a well site that is flaring, with a cargo of natural gas. When it reaches its destination it will unload the new, full cargo of natural gas, and take the old, almost empty, cargo with it essentially creating a pipeline. Virtual pipelines do come with their drawbacks. If potential customers for the gas are not within a certain radius the pipeline will not work. Additionally, there are high capital costs associated with setting up the virtual pipeline. According to ADI Analytics, capital and operating costs can be over $6 per mcf, not including feedstock.

Third, gas to wire technology offers a solution to flaring that is currently the most technically and economically viable today. Gas to wire produces electricity that is sold back to the grid or used at the wellhead. Depending on the power generation technology, there is limited processing required to make the natural gas ready for use and it could also cover, and typically produce more, electricity than is required to operate rigs and other well site equipment. One drawback of gas to wire technology is that producers may have to take on the responsibility of selling electricity back to the grid.

Finally, flared gas can be used to produce chemicals. This offers the highest value solution to reducing flaring. Chemicals are also very easy to transport the finished product to market. However, gas to chemicals technology is not very cost effective for small quantities of natual gas. Further, most gas to chemicals technologies require large plants requiring significant capital. Finally, most gas to chemicals technologies at the small scale are still under development and carry significant technology risk.

Conceptually, there are several options to reduce flaring. However, there are significant challenges in adopting them commercially. Further, implementing any technology will have costs associated with it that are, at the moment, relatively unknown. New standards, such as the goals set by the NDIC, will be the main driver for these new technologies and processes.

-Tyler Wilson and Uday Turaga