After the Paris Agreement entered into force and became a legally binding international treaty on climate change in 2016, 193 signatories were tasked to develop an approach toward successfully reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Solutions exist today to reduce emissions rapidly while supporting economic growth and improving quality of life, but they are not yet implemented at the scale required to make a significant reduction in GHG emissions. One solution that has been gaining momentum in the private sector the last two years is a voluntary carbon offset.

A voluntary carbon offset is the removal of carbon dioxide (CO2) from the atmosphere or the reduction of greenhouse gases that is used to voluntarily compensate for emissions that are occurring somewhere else. Companies in industries where GHG emissions are unavoidable such as the cement, shipping, and chemical industries commonly purchase and claim carbon offsets to become “net-zero”, meaning that their day-to-day operations do not add towards the CO2 emissions being emitted to the atmosphere by balancing their internal emissions with a CO2-reduction project elsewhere. However, there needs to be a causal connection between a company’s purchase of carbon offsets and the actual removal/reduction of CO2 to validate the claim. Otherwise, companies that are claiming these carbon offsets are claiming spurious emission reductions, which only instills more doubt on the legitimacy of the carbon offset market.

Carbon offsets are a topic of contentious, even vitriolic, discussion due to the strongly opposing views of their effectiveness. Advocates for the widespread purchase of carbon offsets believe that they prove their intended purpose. Meanwhile, skeptics believe that buying carbon offsets remain a “roll of the dice” when it comes to climate change impact due to the challenges of quantifying and tracking something that is intangible.

Therefore, emission reduction and carbon sequestration projects must overcome the following obstacles to qualify as a legitimate offset:

- Quantifiability – If the volume of CO2 emissions reduced or the volume of CO2 sequestered cannot be measured with some degree of accuracy, there is no way to award offset credits.

- Verifiability – If the volume of CO2 emissions reduced or the volume of CO2 sequestered cannot be tracked, there is no way to avoid offset fraud, e.g., selling the same offset to multiple buyers.

- Leakage – If an offset is meant to protect a piece of land from an activity that causes GHG emissions, but that activity is displaced to another piece of land, then that’s considered “leakage”.

- Permanence – If you plant trees to sequester carbon, and they burn down 20 years later, that is a permanence failure that undermines the climate change benefit of the project.

- Additionality – If the volume of CO2 emissions reduced or the volume of CO2 sequestered can be tracked back to the existence of, operation of, or financial incentives created by a carbon market, whether voluntary or regulated.

Out of all challenges, additionality is the biggest obstacle for carbon offset markets. The nature and magnitude of the additionality challenge facing offset markets is not widely understood, even by market participants. There are a lot of discrepancies of what additionality truly means, and offset purchasers have no way of reliably differentiating between additional and non-additional offsets in making their purchasing decision, so carbon offset programs have developed two main approaches: “project-specific” and “standardized” approaches, which aim to facilitate the process of determining the additionality of a project.

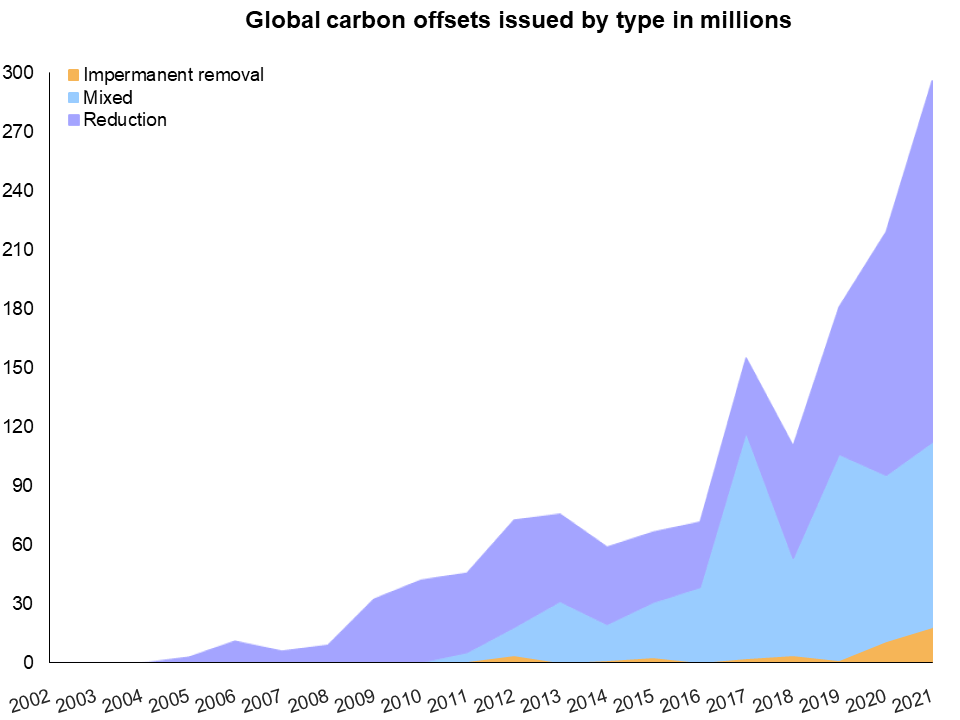

Despite the challenges the carbon offset market faces, the number of carbon offsets issued has more than quadrupled over the last seven years. Carbon dioxide reduction projects accounted for 62% of the carbon offsets issued globally, while mixed projects (reduction and removal) accounted for 32%, and removal projects accounted for 6% during 2021.

Exhibit 1: Global carbon offsets issues by type in millions (Source: University of California – Berkeley)

The growth in carbon offsets issued globally has been astonishing, especially with large corporations such as Alphabet, Stripe, Shell, and Salesforce making carbon reduction commitments by buying carbon offsets. However, better protocols for validating the claims made by carbon offset buyers are necessary to truly drive them as a foolproof solution to reducing CO2 emissions. As the signatories of the Paris Agreement further update their nationally determined contributions (NDCs) for 2025, more and more countries could potentially include carbon offsets as one of the key solutions toward addressing climate change.

If you are interested in learning more about emerging markets driven by the energy transition, such as the carbon offset market, please contact us at ADI Analytics which has been researching and consulting in these areas for a wide range of clients.

– Jacqueline Unzueta