The United States has started exporting LNG, thanks to the cheap and abundant supply of natural gas from shale plays. The first round of LNG exports began from the U.S. Gulf Coast and was quickly followed by a second project on the U.S. East Coast. However, since natural gas supply is now available across the U.S., and key LNG market, e.g., Asia is closer to the U.S. West Coast, an LNG project there should also be conceptually viable. We take a quick look and compare the viability of LNG export projects on the U.S. East and West coasts and compare them to the economics of LNG exports from the U.S. Gulf Coast.

U.S. Gulf Coast: The first LNG exports from the U.S. began in February 2016 from Cheniere’s Sabine Pass terminal located in Cameron Parish, Louisiana. Sabine Pass now delivers LNG to 25 different countries across the world and the volume of LNG shipped from the terminal will continue to increase as more LNG trains are underway. Further, Cheniere is building another export terminal, Corpus Christi LNG, located on the La Quinta Channel in San Patricio County, Texas. Several other LNG export projects have also been announced on the Gulf Coast.

U.S. East Coast: The second terminal that began exporting LNG in April 2018 is Dominion Energy’s Cove Point located in Lusby, Maryland on the U.S. East Coast. The terminal is supplied by Dominion Cove Point Pipeline (DCPL) which sources natural gas supplies from the Marcellus and Utica through Transco and Columbia Gas (TCO) pipelines. U.S. East Coast LNG terminals can benefit from cheap gas supplies from Marcellus and Utica as well as shorter shipping distances to Europe relative to LNG supply from the U.S. Gulf Coast. As a result, there is interest in additional LNG terminals on the U.S. East Coast. For example, Penn America Energy has announced the Penn LNG project on the Delaware River with plans for start-up in 2024.

U.S. West Coast: Finally, Jordan Cove is an LNG terminal that has been proposed on the U.S. West Coast located in the Coos Bay in Oregon. Natural gas supplies to the LNG terminal will come either from the U.S. Rockies via the Ruby Pipeline or the Gas Transmission Northwest (GTN) pipeline from British Columbia both of which terminate in Malin hub in Oregon. Natural gas from Malin, Oregon will feed into the Pacific Connector Gas Pipeline which will go directly to Jordan Cove.

However, the proposed Pacific Connector Gas Pipeline project is facing significant opposition from local tribes. If completed, it might become the best-positioned terminal in the U.S. to serve markets in Asia because of its shorter shipping distance to Asia compared to other terminals in the U.S.

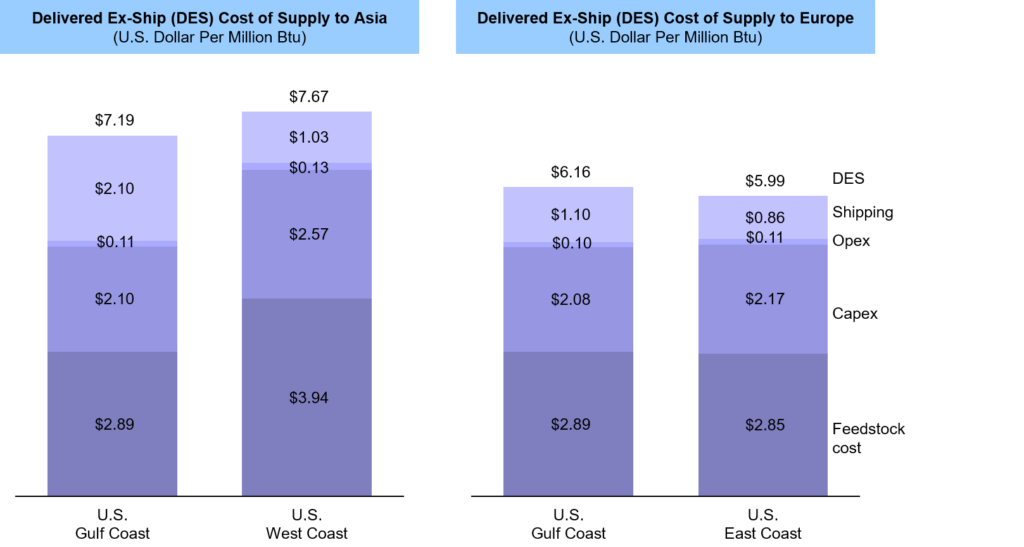

We have analyzed and compared in Figure 1 the economics of LNG exports – in terms of delivered ex-ship (DES) costs for LNG – from these three locations to Asia and Europe. The DES cost includes feedstock cost, operating cost, shipping cost, and capex recovery cost. Some component costs such as feedstock and shipping costs depend on multiple variables such as access to natural gas supply, ship charter rates, utilization levels, canal costs, and voyage times.

Figure 1. U.S. Delivered Ex-Ship (DES) Cost of Supply

Figure 1 shows that LNG export projects on the U.S. Gulf Coast will continue to be very competitive in serving both Asia and, potentially, even Europe primarily due to access to natural gas and lower capital costs. Pipeline transportation expenses are high on the U.S. West coast since they are not close to any of the leading gas shale plays which leads to a higher feedstock charge compared to that on the U.S. Gulf coast. For LNG shipments to Europe, U.S. East Coast projects have a marginal advantage due to lower shipping costs.

ADI Analytics continues to monitor the developments in the LNG industry. We recently published a multi-client study, Micro-, Small-, and Mid-Scale LNG in North America, which looks at several key issues in the industry. Please contact us to learn more about our research.

– Uday Turaga and Palak Puri