While 90% of alumina is used for aluminum production, alumina can be used in industrial abrasives, refractories, glass, and engineered ceramics. Alumina is primarily derived from bauxite ore through a series of chemical reactions known as the Bayer process. The alumina produced through the Bayer process is in the form of a white powder, but it can be processed into other forms depending on its intended use. One of the challenges alumina producers face with the Bayer process is the inevitable production of red mud. Red mud is an unwanted by-product of the Bayer process which is discarded by alumina producers. Due to its composition and high alkalinity, red mud is considered an environmental hazard.

Due to the unwanted production of red mud, efforts to commercialize other sources of alumina are underway. Vast resources of clay are technically feasible sources of alumina, but not economically competitive. Currently, bauxite is the only source used for commercial-scale production of alumina. Countries rich in bauxite resources include Australia, China, Guinea, Brazil, India, and Indonesia. Of the bauxite-rich countries, China is the leading producer of alumina and Guinea is the world’s second largest producer of bauxite. China uses most of their alumina production to produce aluminum.

Currently, aluminum prices are at a decade high following news of a coup in Guinea. According to the London Metal Exchange, a metric ton of aluminum is worth $2,776. President Alpha Condé has been overthrown in an apparent military coup, and many are concerned about the supply of bauxite. Due to the new political regime, commodity export disruptions will occur, and renegotiations will need to be made between China and Guinea. Twenty-five percent of the world’s supply of bauxite comes from Guinea, which is predominantly exported to China and Russia. Guinea is China’s largest source of bauxite, but will the demand for Guinea’s bauxite weaken as China sets to achieve its sustainability goals?

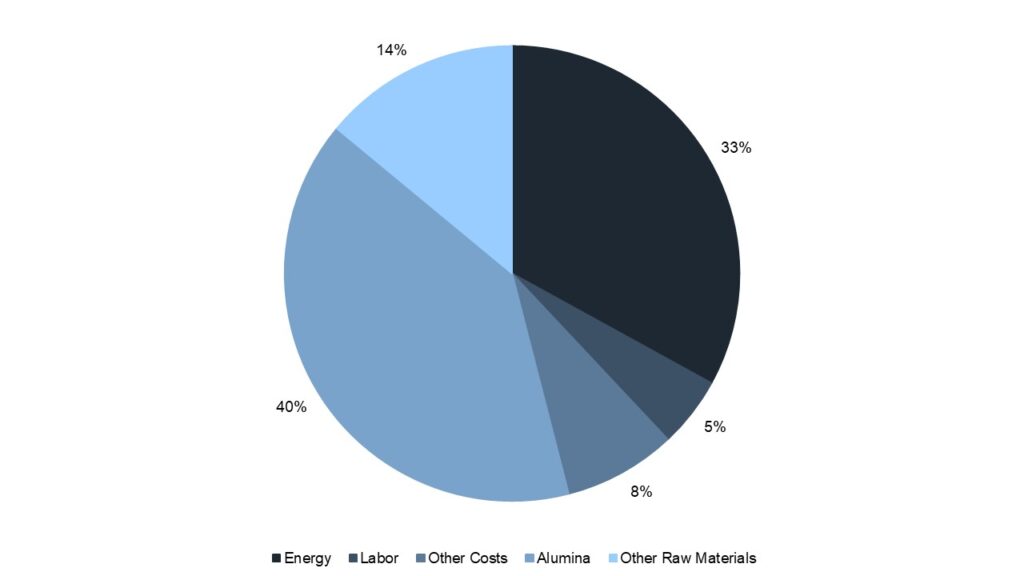

China’s emission regulations and carbon neutral 2060 targets may heavily impact aluminum production, thus impacting alumina production and bauxite demand. Primary aluminum production requires a lot of energy and is CO2 intensive. In fact, the cost of energy accounts for 33% of the total production cost of aluminum (Exhibit 1).

Aluminum is the most carbon-intensive metal by producing 15-20 metric tons of CO2 per ton of aluminum produced. China is a net aluminum exporter, and a material tightening effect has already been seen in Inner Mongolia during the first quarter of 2021. As an environmental effort, Inner Mongolia has ordered several aluminum plants to reduce production, thus reducing their coal consumption. Consequently, aluminum exports from China are expected to decline within the next five to ten years. This introduces an opportunity for other aluminum producers to capitalize their aluminum production using large renewable power-based production. Two companies outside of China that are well-positioned for this opportunity includes Norsk Hydro and Rio Tinto.

Despite the restrictive effects environmental regulations may have on China’s alumina supply, China is expected to grow its capacity by approximately 12.5 million metric tons by 2025. China would then have sufficient capacity to meet projected demand and lift alumina exports that could push the seaborne market into oversupply. However, this is unlikely, and the most probable outcome is that China will limit their alumina production for domestic use rather than exporting alumina overseas. China may also further reduce their alumina production if it can purchase alumina from the seaborne market at a lower price.

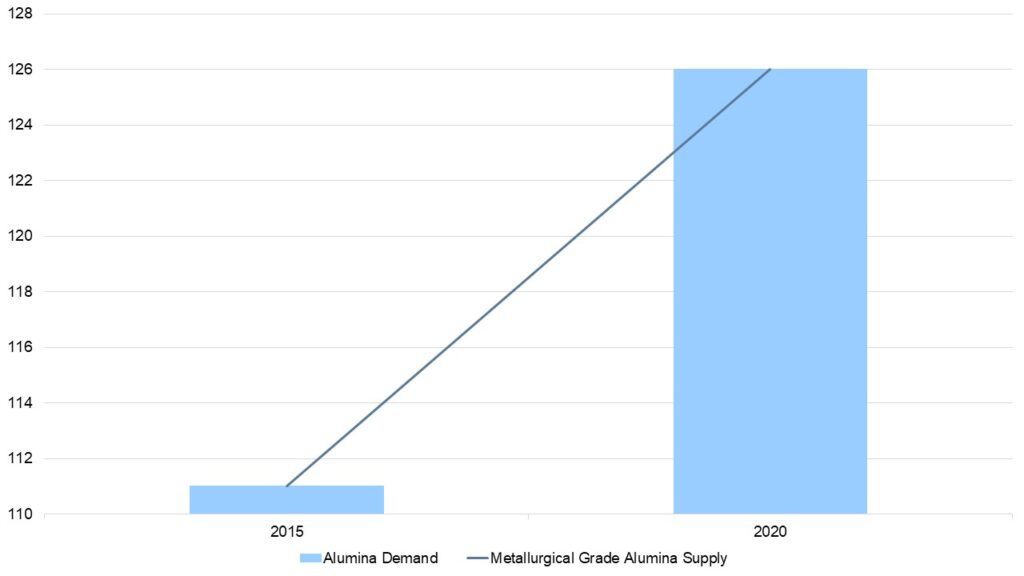

The global alumina market is expected to remain in a surplus over the next three years, but the balance is expected to narrow in succeeding years (Exhibit 2). Currently, ex-China supply is recovering from COVID-19 disruptions and from the outage at the Alunorte refinery in Brazil during the second half of 2020, which returned to full capacity in late 2020. A full ramp-up of the Al Taweelah refinery in UAE and some reactivations of European refineries are expected during the second half of 2021. The increase in supply is expected to be approximately 7 million metric tons between 2020 and 2021.

Global alumina demand is expected to grow at an annual growth rate of 1.8% to 143 million metric tons in 2025 from 133 million metric tons in 2021. Prices for alumina may be capped at China’s marginal cost of about $300/t if China decides to purchase cheaper alumina from the ex-China market. However, assuming China becomes self-sufficient in alumina and the ex-China market continues to grow, higher prices (> $350/t) may be needed to incentivize new refineries in the rest of the world to meet future alumina demand growth.

Any change in the global bauxite market will affect the alumina market, which will affect the aluminum market and conversely. These three global markets and their end-user markets are all intertwined, so the coup in Guinea and China’s sustainability measures are expected to have an immense hit across various markets. The future of the bauxite, alumina, and aluminum markets is still uncertain, but speculators predict higher prices across the board.

On the bright side, the leveled playing field introduces new opportunities for Australia, the largest producer of bauxite. Recently, shares in Australian bauxite miners rose substantially, with Alumina Ltd up 3% on the Australian Stock Exchange. Rio Tinto, an Anglo-Australian miner, may also capitalize on these disruptions as it operates several large bauxite mines in Australia and Brazil. More disruptions may arise, but new opportunities come to light leaving a lasting impact on the global competitive landscape.

– Jacqueline Unzueta