The week began with chatter on IEA’s Net Zero to 2050 Roadmap – it calls for a complete stop on upstream oil & gas investment starting this year – but is ending with a ruckus as shareholders have elected new directors opposed by the company to ExxonMobil while asking Chevron to start preparing to cut Scope 3 emissions. Separately, a court in The Hague has ordered Shell to cut net carbon emissions mandating them to be lower by 45% in 2030 relative to their levels in 2019.

While all of this is not really new to oil & gas market analysts like us at ADI Analytics, the steady drumbeat of calls on oil & gas operators to prepare for the energy transition is with this week’s developments a deafening crescendo that cannot be missed or ignored. What does this new climate for Oil & Gas mean?

1. Investors are leading the charge for change. Oil & gas operators are used to pressure on these issues from regulators but this is an investor-led rebellion. Scared at the prospect of being stranded with portfolios comprising distressed oilfields, refineries, and pipelines that no one will buy, investors are calling for meaningful energy transition strategies. In comparison, the policy and regulatory framework is lagging behind, at least, in the U.S. although that may change under the Biden Administration. Unfortunately, waiting for policy and regulatory support to act may be too late.

2. Delivering returns is no longer sufficient. Many industry insiders have tried to explain ExxonMobil’s challenges with delivering returns — ~28% over 2009-19 versus Chevron’s ~118% — in the past decade as the primary driver for its proxy fight with Engine No. 1. However, Chevron which has successfully delivered more than four times ExxonMobil’s returns over 2009-19 is also being asked for significant shifts in their strategy. Oil & gas operators, therefore, cannot simply focus on being the best-cost operator and hope to ride out this onslaught of calls for change.

3. A goal for the distant future ain’t enough either. Similarly, investors and communities are asking for meaningful, deep, and material changes in strategy. Shell should be lauded for pioneering with a handful of its peers on formulating an aggressive energy transition strategy but the court decision in The Hague reflects stakeholders’ desires for more and quicker change. Shell like a number of other oil & gas companies have announced goals to cut carbon intensity – amount of carbon emitted per unit barrel, cubic foot, or joule of energy produced or sold – by 6% in 2023, 20% in 2030, and 45% in 2035 relative to the metric’s value in 2016. Societal pressures will ask oil & gas operators to commit to more and in absolute emission cuts using science-based targets.

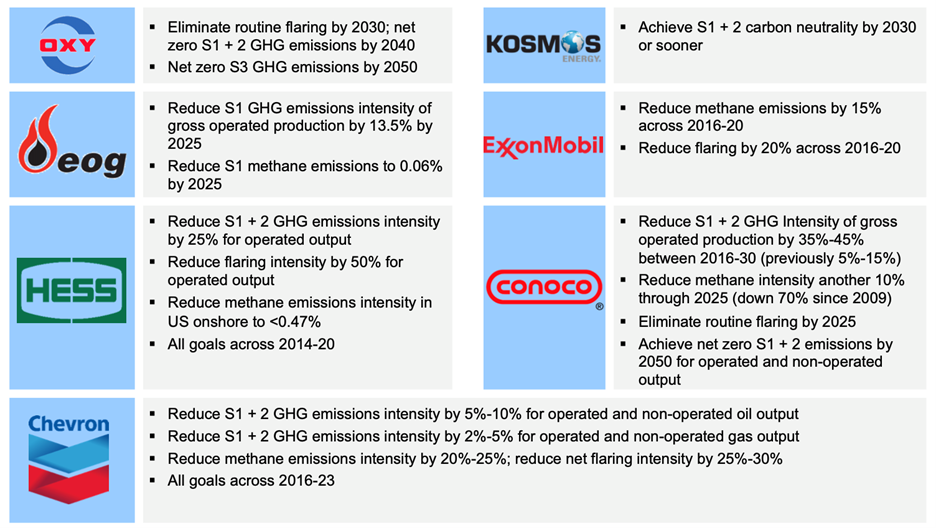

4. Cutting fugitive emissions and flaring won’t suffice either for long. As oil & gas operators think of material shifts to their businesses, several companies have announced goals to cut fugitive methane emissions and natural gas flaring as shown in Exhibit 1. While these are important initiatives that improve the overall sustainability and environmental competitiveness of the industry, the pace of change that is being called for will soon render these initiatives as table stakes and not provide any differentiating comfort. By the same token, R&D collaborations and corporate venturing investments are likely to fall short of stakeholder demands meeting which will require material investments to kick-off new capital projects or acquire companies in energy transition markets.

Exhibit 1. Oil & gas operators that have announced goals to cut emissions.

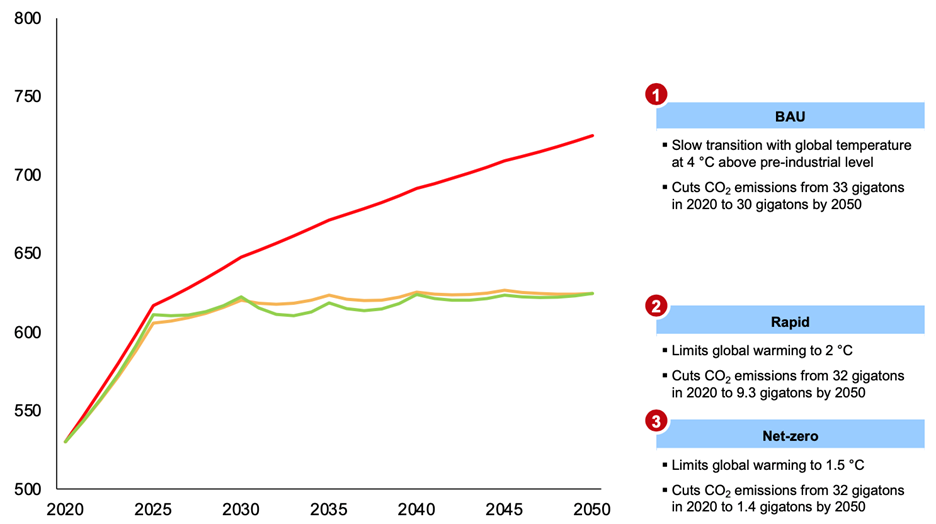

5. Limited opportunity set with a lot of competitors. Energy transition, however, is not an infinite set of opportunities, and, further, as we have written before, a lot of low-/zero-carbon energy projects often have significant investments and returns that are lower than what oil & gas operators have typically delivered. Further, the competition for these projects is rapidly intensifying, and will only grow at a faster pace following the developments of this week. Finally, although the world will need growing supply of energy, meaningful energy transition scenarios will lead to stagnation in energy demand as shown in Exhibit 2 from ADI Analytics’ work. As a result, the traditional argument of relying on growing demand for energy as a driver for the industry to pursue growth may have some limits in the long-term if not in the next decade.

Exhibit 2. Total energy consumption in EJ in various scenarios.

6. Early adopters may be the only survivors. A final thought builds on the point made earlier that most regions barring Europe have limited policy and regulatory pressure on oil & gas operators although it is building. The fact that a lot of the current pressure is from investors and not governments is an opportunity oil & gas operators need to seize. At some point, government policy will evolve that will seriously restrict operation of several kinds of oil & gas facilities. Until then, operators have the opportunity to better define their portfolios and sell marginally-performing assets. As a result, being a fast follower may not be sufficient, and, in fact, only early adopters may survive through this disruption.

News of Engine No. 1’s success first flashed through newspaper notifications on my phone but was soon followed by text messages from clients around the world. My brother-in-law, who began his consulting career by winding down one of the largest tobacco companies, said that the news reminded him of those days. I do not share the view that oil & gas is the new tobacco. This past week signifies an important disruption that has been in the making but oil & gas operators have a number of pathways out towards the energy transition, and I’ll share thoughts on what they can do in the next episode of this blog.

-Uday Turaga