Interest in the energy transition is growing rapidly and investments are following that interest closely as well. In the past year, global oil and gas companies have announced major goals and plans embracing the energy transition and have started ramping up on investments in the power sector, low-carbon technologies, and mobility.

For example, BP has announced plans to invest $5 billion per year to scale up investments in reducing carbon emissions and achieve net-zero emissions by 2030. Similarly, Repsol has committed to becoming a net-zero emission company by 2050 by investing in low-carbon businesses and setting up an internal carbon pricing mechanism. Also, Saudi Arabia will invest $500 billion in the next few years for its most ambitious NEOM project to develop a sustainable smart city fully powered by renewable energy sources. Further, a number of companies in the oil and gas and several other industries have initiated plans to explore, pilot, and develop hydrogen as a fuel for various applications as a strategy for the energy transition.

Carbon dioxide emission reductions will be a key driver for energy transition projects and investments. To that end, the performance, behavior, and incentives of carbon credit pricing will be critical to support and drive energy transition investments and projects. Carbon pricing is a cost that is applied to carbon pollution to encourage industries to reduce the amount of greenhouse gas emissions by tying the costs of carbon to their source through a price, usually in the form of a price on the carbon dioxide emitted. This initiative drives industries to decide the extent to which they can emit carbon and pay for it or stimulate clean technology investments and market and business model innovation and get credits for carbon savings.

There are two main types of carbon pricing models: emissions trading systems (ETS) and carbon taxes. An ETS – sometimes referred to as a cap-and-trade system – caps the total level of greenhouse gas emissions and allows those industries with low emissions to sell their extra allowances to larger emitters. A carbon tax directly sets a price on carbon by defining a tax rate on greenhouse gas emissions.

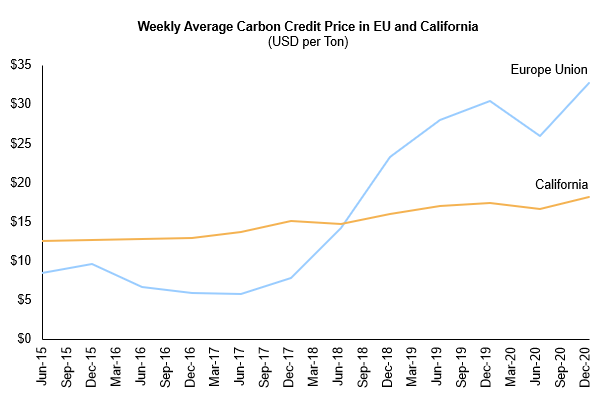

Carbon credit pricing in EU and California in recent years is illustrative of what we can expect. Exhibit 1 shows the weekly average carbon credit price in Europe and California over the past five years. It seems that carbon pricing is rising in both markets and we expect the trend to continue in the coming years.

Exhibit 1: Weekly average carbon credit price in the EU and California in USD per ton of CO2 emission

A progressively increasing carbon price will provide essential confidence for investment in long-lived, low-carbon infrastructure and research, development, and demonstration of clean energy technology. The right level of carbon pricing gives emitters the policy certainty that high-carbon investments are less attractive than low-carbon alternatives. The rise in carbon credit pricing also reflects a few key market dynamics:

- Demand for carbon credits is rising or expected to rise as energy transition pressures across broad sectors and economic regions, e.g., Europe will lead companies that fall short of carbon caps to procure them to comply with regulations or their own targets.

- Credit supply in a world preparing for energy transition should go up but will need capital investments that have to be incentivized by high carbon credit prices. As a result, this will occur at an uneven pace with significant levels of uncertainty in the outlook going forward.

- Carbon utilization will become increasingly important going forward and the current COVID-19 pandemic and oil price crash pose their own challenges. For example, the Petra Nova project, supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, demonstrated how carbon capture, utilization, and storage technologies can economically support the flexibility and sustainability of fossil fuels at commercial scale. However, the project has stopped operating because low oil prices have made it uneconomic to sell carbon dioxide to boost oil drilling operations. Similarly, ethanol producers, which supply 40% of merchant-based CO2 in the U.S., are evaluating possible CO2 revenue and tax credit opportunities as a means of both monetizing the product or even reduce emissions via various sequestration schemes which offer tax credits. On the other hand, the COVID-19 pandemic has led to the shutting down of several ethanol plants in U.S. disrupting the CO2 supply.

- Finally, regulations and incentives will play an important role in moving forward. For example, under the 45-Q tax credit rule, industrial manufacturers in the U.S. that capture carbon from their operations can earn $50 per metric ton of CO2 stored permanently or $35 if the CO2 is put to use such as for enhanced oil recovery (EOR). To incentivize carbon capture, the tax credits go directly to the entity doing the capture.

These are a few illustrations of how carbon credits will play a critical role in the energy transition. Future ADI blog posts will dive deeper into some of these dynamics building on ADI’s extensive research and consulting work across a broad range of energy transition topics. Please contact us to learn more about ADI’s prior consulting work and research capabilities around energy transition.

-Utkarsh Gupta and Uday Turaga