Last week, it was announced that Halliburton would not be following through with its acquisition of Baker Hughes. Meanwhile, in early April, Schlumberger’s acquisition of Cameron was completed. Understanding why the Halliburton Baker Hughes deal fell through while the Schlumberger Cameron deal moved forward offers insight into the outlook for M&A in oilfield services.

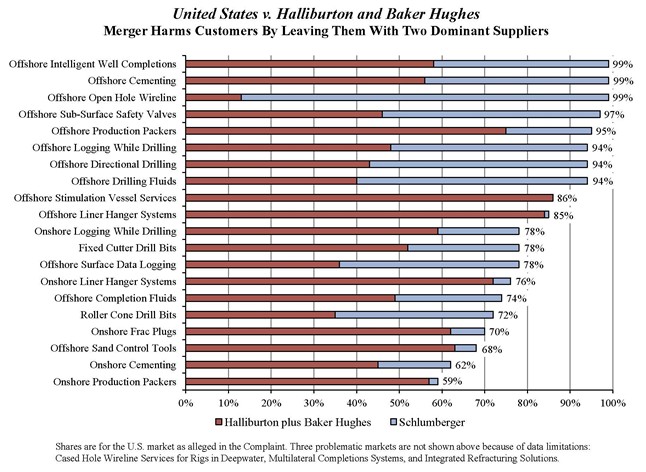

Fundamentally different deals: The Halliburton Baker Hughes merger fell mainly due to the scrutiny of both European and U.S. regulators. Regulators were concerned that the consolidation of two of the three largest oilfield services companies would lessen competition and stifle innovation across 23 oilfield products and services such as on and offshore production packers, well completions, and well stimulation. In other words, there were many overlapping business segments between Halliburton and Baker Hughes. Efforts to sell some of the overlapping businesses to third parties did not succeed due to low oil prices. Figure 1 shows the different markets where Schlumberger and the combined Halliburton Baker Hughes entity would have dominated market share. (Source: United States Department of Justice)

Figure 1

On the other hand, Schlumberger’s acquisition of Cameron was not so much a consolidation of services as it was an expansion of offerings. There was little overlap between Schlumberger’s and Cameron’s product and service offerings. Schlumberger was looking to create a complete drilling to production offering by combining in-house reservoir technology with Cameron’s wellhead and surface technologies.

There will likely be less mergers than acquisitions moving forward: We believe the outlook for mergers in oilfield services is not promising in spite of low oil prices and attractive valuations because of four reasons.

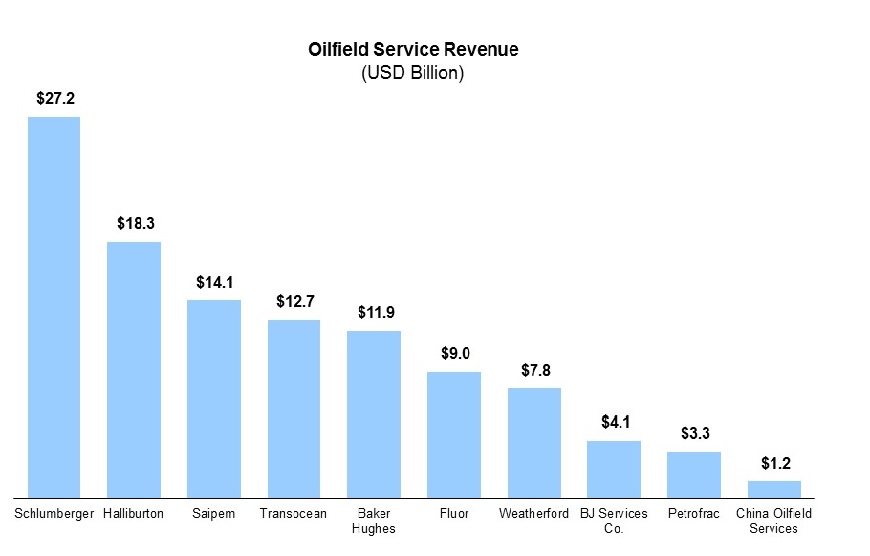

First, the oilfield service market is not as fragmented as widely believed. There are about ten companies worldwide with more than $1 billion USD in annual revenues from oilfield services with five of those having more than $10 billion USD in annual revenue. This limits the pool of acquisition targets and particularly so for companies with market capitalization from ~$1 to $10 billion. Figure 2 shows the top ten public oilfield service companies by annual revenue.

Second, is regulatory scrutiny. As with Halliburton and Baker Hughes, a merger is much more likely to further consolidate the market in a manner that regulators will deem harmful than an acquisition like that of Cameron by Schlumberger. Regulators are seeking to protect consumers from over-consolidation that would lead to enable a smaller number of firms to set prices rather than have the free market determine prices. The U.S. Department of Justice claimed that stopping the Halliburton Baker Hughes merger was a large victory for the U.S. consumer as the deal would have likely led to increased energy costs.

Third, the bid / ask spread for companies is still very wide. This discrepancy comes due to the drop in the price of oil. Valuations of oilfield service companies are closely correlated with the price of oil and those looking to buy an oilfield service company are valuing the prospective acquisition much lower than the seller. A seller will likely argue that their company is worth more with the assumption that oil prices will rise in the coming years. Buyers, however, do not want to pay for a company based on the speculative future price of oil.

Finally, there are a lot of companies in distress and are already bankrupt or heading towards bankruptcy. A lot of such companies are looking attractive to buyers with the wave of high bid / ask spreads. Further, there’s three to four times more capital available than during the last oil downturn enabling investors to consider buying distressed assets and recapitalizing them. Additionally, the cost of capital has been low for an extended period of time giving buyers more leverage when purchasing or recapitalizing a distressed asset.

In all, even with lower valuations and a surplus of capital it is unlikely that there will be a large amount of M&A activity in oilfield services. This is primarily due to regulatory pressures in an already consolidated market struggling with low oil prices, high bid / ask spreads, and plenty of distressed assets.

-Tyler Wilson and Uday Turaga